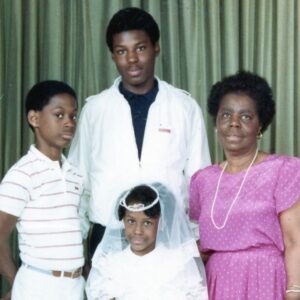

I grew up without a father. My grandmother raised my brother, my sister, and me. In my Brooklyn neighborhood during the ’70s and ’80s, not having a father was the norm. But just because it was common didn’t mean it was right.

Growing up in a single-parent household, I lacked the understanding of the little things that a two-parent household brings. I never saw how a loving Black husband and wife interacted with one another and with their children. The first time I saw what that kind of love looked like was James and Florida Evans on Good Times, but it was on The Cosby Show, watching Dr. Huxtable and Clair Huxtable, that it really hit home. Their love was so foreign to me—so gentle, patient, and kind. It was something I had never experienced in my own home.

No one in my household ever said “I love you” out loud to one another, and discipline was always physical for us. My grandmother sacrificed so much when she took us in, but her lack of outward expressions of love has haunted me over the decades.

I once asked her if something had happened in her life that made her raise us the way she did. She answered, and though I’m paraphrasing as best I can, her words still echo in my mind:

“I had a life before you came into it. I had a man who I loved, and he loved me back unconditionally. I chose you and your siblings over that man. And I would do it again, every day, in every lifetime. The truth is, I’m over 100 years old, and every day I’m still affected by the trauma I endured from my own childhood.”

Hearing her say that gave me insight into the depth of her sacrifice, but it also made me reflect on the emotional gaps I’ve carried with me. While my grandmother did her best, I often wonder if children raised in two-parent households adapt to society differently. Do they have an advantage when it comes to understanding love, vulnerability, or even how to express themselves emotionally?

After I was incarcerated, I began to realize that I lacked the basic fundamentals to sustain a healthy relationship. It was hard for me to say “I love you.” It was hard for me to take my woman in my arms and hold her tightly—just because. I still have trust issues that I attempt to deal with on a daily basis. But I’ve made a conscious effort to change.

Now, I go out of my way to say “I love you” to my children. I step out of my comfort zone to smother them with hugs and kisses. I make sure to tell my wife “I love you” every day. I know my grandmother meant well—by taking us in and providing for us, she was showing us she loved us the best way she could. But I’m determined to go the extra mile for my family to make sure they know they are loved.

I’m still healing, but knowing I am breaking a generational curse is my way of saying “I love you” to my grandmother.

“My hustle is writing—I am a writer!

If this post resonated with you, check out my eBook, Miracle at Cana, on Amazon. It’s another piece of my journey, and I hope it inspires you to keep pushin’ forward. Click here to grab your copy: Miracle at Cana.